Marcus A. Templar

Marcus A. Templar By Marcus A. Templar

Abstract

The focus of this monograph is to offer a simple understanding to those unfamiliar with the issue of national security as related to disciplines of Strategic Intelligence, the collection of information, its analysis, and exploitation for the benefit of a state’s national security as it fulfills the satisfaction of its national interests.

In his book Espionage and Treason, the late André Gerolymatos articulated the role of proxeneia in Classical Greece (Gerolymatos 1986). The book offers Gerolymatos’ excellent understanding of how diplomatic missions worked and still do. Nevertheless, espionage is a term that covers a variety of actions employed by states for a wide range of reasons and does not cover the full scope of the tradecraft.

The correlation between intelligence and, more specifically, strategic intelligence and national security is coefficient and mutually dependent. This monograph has used the core of a speech under the title Intelligence in Contemporary America that the author had delivered at the Kiwanis Club on December 2, 2019.

What is Intelligence?

The definition of intelligence has troubled many intelligence professionals throughout the years, especially those who understand the full scope of their tradecraft. Even professionals shrink from answering the question “what is the definition of intelligence” and rightly so. Nevertheless, to an intelligence professional who has worked in that specific part of National Security, the simple definition of intelligence is the analysis of carefully collected information free of contaminated and inaccurate material. It includes objectivity independent of political considerations based on all available credible sources and timeliness.

It is true that in some cases, the analyst might seriously consider information collected from dubious informants with sketchy motives or documents of unknown origin because they match some person’s beliefs. It is the case that verification for the accuracy of such information is of great importance. It is not unusual that adversaries intentionally or sometimes unintentionally release essential details of certain subject matter. One may also receive speculative or unreliable information pushed in by politically motivated personnel, most of whom are appointees to please the boss. Conspiracy theories are not part of reliable intelligence. To avoid mishaps, a departmental fusion process exists. Agencies propel the evidence to the Office of National Intelligence, where specific information gets an exhaustive examination that follows by a thorough sanitization.

Knowing oneself and one’s adversary is extremely important in intelligence. A significant advantage of an intelligence officer is not only to know what one knows, but to know what one does not know, i.e., one must attain the psychological stage of Conscious Competence. It is the stage in which one knows what one knows, but most importantly one knows what one does not know.

Sun Tzu, the Chinese general, military strategist, writer and philosopher who lived in the Eastern Zhou period of ancient China, and author of The Art of Warfare, states in Section III, “Attack by Stratagem”, “If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle” (The Book of War 2000, 80-81).

In Ancient Times

The Book of Numbers

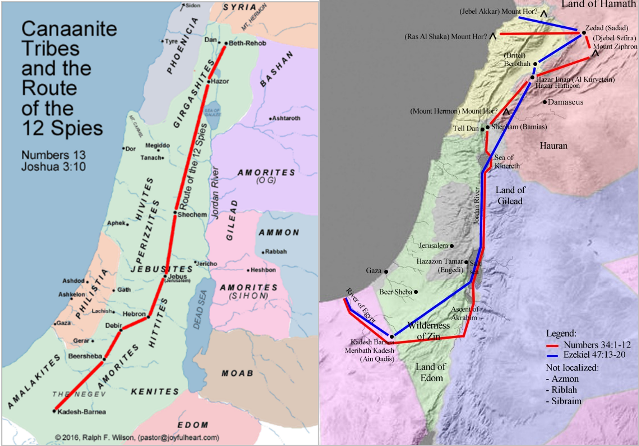

The first recorded example of intelligence collection comes to us from the book of Numbers (Hebrew: Bəmiḏbar meaning "In the desert") is the fourth book of the Tanakh and the fourth of five books of the Torah.

According to the text (chapter 13), Moses sent 12 men to spy on the inhabitants and land north of Kadesh Barnea, which was at the edge of the desert of Paran, where the Israelites were encamping (Numbers 10:12; 12:16). The 12 men journeyed north to Hebron, and from there, they traveled north toward the valley of Eshkol and then the hill country, i.e., around present-day Jerusalem and beyond exploring the territory up to the Heights of Golan near the present-day Quneitra, Syria.

After the scouts had explored the entire land, they returned to Kadesh Barnea where two of the spies, Joshua and Caleb, reported that the area was abundant "flowing with milk and honey, probably a date syrup. The members of the reconnaissance team brought “back samples of the fruit of the land, most notably a gigantic cluster of grapes which requires two men to carry it on a pole between them.” Nevertheless, they also reported that the people who dwelt in the land were strong; the cities were fortified, and also, the cities were huge, but compared to what? Ten out of 12 mentioned that the people of those cities were giants and also reliable, kind of cruel, bogeymen, and hobgoblins. However, the twelve spies cataloged the human terrain, i.e., the inhabiting tribes and the specific locations of their habitation.

Such are the problems an intelligence analyst faces daily since it crucial that one decides what is factual and fictional. What the 10 out of the 12 men had reported about the “giants” is a matter of opinion or a case of exaggeration out of fear or unwillingness to fight them. These were the Israelites who were born in captivity. They had learned to be subservient instead of fighting for their rights. After this occurrence, God punished all of them by keeping them in a place for 40 years so that those who were born in captivity, in Egypt, die and the new generation who was born in the wilderness and free not knowing enslavement were ready to fight and win (Num. 32:13).

The above is the first example of human intelligence of tactical, operational, but most importantly of strategic value. The answers Moses received were enough to assess the risk but also to design the path. Per God’s instructions, Moses assigned the leaders of each tribe to deploy, coordinate, and participate in the tactical on the ground situation.

The team of scouts produced intelligence by querying information repositories and generating reports. The scouts devised methods for identifying factual patterns and trends in available sources of information. They also determined capabilities, vulnerabilities, and probable courses of action of their adversaries. They acquired the psychological aspects of the people and what made them tick.

Abstract

The focus of this monograph is to offer a simple understanding to those unfamiliar with the issue of national security as related to disciplines of Strategic Intelligence, the collection of information, its analysis, and exploitation for the benefit of a state’s national security as it fulfills the satisfaction of its national interests.

In his book Espionage and Treason, the late André Gerolymatos articulated the role of proxeneia in Classical Greece (Gerolymatos 1986). The book offers Gerolymatos’ excellent understanding of how diplomatic missions worked and still do. Nevertheless, espionage is a term that covers a variety of actions employed by states for a wide range of reasons and does not cover the full scope of the tradecraft.

The correlation between intelligence and, more specifically, strategic intelligence and national security is coefficient and mutually dependent. This monograph has used the core of a speech under the title Intelligence in Contemporary America that the author had delivered at the Kiwanis Club on December 2, 2019.

What is Intelligence?

The definition of intelligence has troubled many intelligence professionals throughout the years, especially those who understand the full scope of their tradecraft. Even professionals shrink from answering the question “what is the definition of intelligence” and rightly so. Nevertheless, to an intelligence professional who has worked in that specific part of National Security, the simple definition of intelligence is the analysis of carefully collected information free of contaminated and inaccurate material. It includes objectivity independent of political considerations based on all available credible sources and timeliness.

It is true that in some cases, the analyst might seriously consider information collected from dubious informants with sketchy motives or documents of unknown origin because they match some person’s beliefs. It is the case that verification for the accuracy of such information is of great importance. It is not unusual that adversaries intentionally or sometimes unintentionally release essential details of certain subject matter. One may also receive speculative or unreliable information pushed in by politically motivated personnel, most of whom are appointees to please the boss. Conspiracy theories are not part of reliable intelligence. To avoid mishaps, a departmental fusion process exists. Agencies propel the evidence to the Office of National Intelligence, where specific information gets an exhaustive examination that follows by a thorough sanitization.

Knowing oneself and one’s adversary is extremely important in intelligence. A significant advantage of an intelligence officer is not only to know what one knows, but to know what one does not know, i.e., one must attain the psychological stage of Conscious Competence. It is the stage in which one knows what one knows, but most importantly one knows what one does not know.

Sun Tzu, the Chinese general, military strategist, writer and philosopher who lived in the Eastern Zhou period of ancient China, and author of The Art of Warfare, states in Section III, “Attack by Stratagem”, “If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle” (The Book of War 2000, 80-81).

In Ancient Times

The Book of Numbers

The first recorded example of intelligence collection comes to us from the book of Numbers (Hebrew: Bəmiḏbar meaning "In the desert") is the fourth book of the Tanakh and the fourth of five books of the Torah.

According to the text (chapter 13), Moses sent 12 men to spy on the inhabitants and land north of Kadesh Barnea, which was at the edge of the desert of Paran, where the Israelites were encamping (Numbers 10:12; 12:16). The 12 men journeyed north to Hebron, and from there, they traveled north toward the valley of Eshkol and then the hill country, i.e., around present-day Jerusalem and beyond exploring the territory up to the Heights of Golan near the present-day Quneitra, Syria.

After the scouts had explored the entire land, they returned to Kadesh Barnea where two of the spies, Joshua and Caleb, reported that the area was abundant "flowing with milk and honey, probably a date syrup. The members of the reconnaissance team brought “back samples of the fruit of the land, most notably a gigantic cluster of grapes which requires two men to carry it on a pole between them.” Nevertheless, they also reported that the people who dwelt in the land were strong; the cities were fortified, and also, the cities were huge, but compared to what? Ten out of 12 mentioned that the people of those cities were giants and also reliable, kind of cruel, bogeymen, and hobgoblins. However, the twelve spies cataloged the human terrain, i.e., the inhabiting tribes and the specific locations of their habitation.

Such are the problems an intelligence analyst faces daily since it crucial that one decides what is factual and fictional. What the 10 out of the 12 men had reported about the “giants” is a matter of opinion or a case of exaggeration out of fear or unwillingness to fight them. These were the Israelites who were born in captivity. They had learned to be subservient instead of fighting for their rights. After this occurrence, God punished all of them by keeping them in a place for 40 years so that those who were born in captivity, in Egypt, die and the new generation who was born in the wilderness and free not knowing enslavement were ready to fight and win (Num. 32:13).

The above is the first example of human intelligence of tactical, operational, but most importantly of strategic value. The answers Moses received were enough to assess the risk but also to design the path. Per God’s instructions, Moses assigned the leaders of each tribe to deploy, coordinate, and participate in the tactical on the ground situation.

The team of scouts produced intelligence by querying information repositories and generating reports. The scouts devised methods for identifying factual patterns and trends in available sources of information. They also determined capabilities, vulnerabilities, and probable courses of action of their adversaries. They acquired the psychological aspects of the people and what made them tick.

They then communicated to Moses and through him possible suppliers, and others to stay abreast of industry or business trends. In this manner, they developed the strategic analysis that became the cornerstone of strategic planning that led the Israelites to the promised land.

Sinon (Σίνων), the Double Agent

As an example of a double agent in the ancient world, but also of selfless dedication to the cause, we take the situation in the Trojan War and the Wooden Horse or as I call it the Greek Horse. His name was Sinon (Greek: "Σίνων"), and he was a relative of Ulysses. Although Homer does not mention Sinon’s name, he does mention the incident with the Horse. Sinon’s name comes to us from Virgil’s book of Aeneid II, 77, but also Quintus of Smyrna. The details of the story appear in Aeneid, book 2, 77, but also in chapter 12 of Quintus of Smyrna in his Post-Homerica.

After Ulysses put the plan down, the task building of the horse was given to an excellent carpenter and skilled boxer (Iliad XXIII) from Phocis, Epeius (Ἐπεύς or Ἐπειός) who told the Greek leadership of the design, the quality and quantity of logs needed for the project. The Greeks went to mountain Ida (presently Turkish: Kazdağı = goose mountain) just southeast of Troy (Turkish Truva) for the timber. Epeius built the horse with a hollow belly so that several warriors could fit in it. We know of the names of 30 warriors who entered the belly of the horse. Epeius was the last one to enter the horse through one of the doors.

After the horse was finished and the warriors entered the hollow horse, the Greek fleet sailed and hid behind the island of Tenedos, but not before they left a wandering warrior at the hills of near Troy. His name was Sinon. Sinon had volunteered for the mission knowing full well that he would be tortured and even killed by the Trojans.

Quintus of Smyrna states that the Trojans woke up in the morning getting ready to attack, but they could not see anyone there except for one man, Sinon, next to the wooden horse. The camp was deserted, and one could see only smoke coming from the Greek campsite. Apollodorus (5.14–5.18) states that Sinon was the one who started the fire only to attract the attention of the Trojans to him.

In the beginning, the Trojans encircled him and gently asked him questions, which he refused to answer. Then the Trojans grew angry and began to threaten him with stabbing. Sinon remained defiant to their threats, not answering their questions. As a means of unfriendly persuasion, the Trojans cut off his ears and then his nose. Finally, under pressure, he told them the pre-rehearsed story, i.e., the Greeks had fled, and they built the Trojan Horse to honor Athena.

According to Quintus of Smyrna (chapter 12), Sinon claimed that Ulysses (Odysseus) wanted to sacrifice him, but he managed to escape and hid in a swamp. When the Greeks gave up looking for him and left, he returned to the Trojan Horse adjacent to the camp. Sinon claimed that out of respect for Zeus, the Greeks stopped looking for him. All the Trojans believe this story, except Laocoön, who, along with his two sons, who were attacked by a giant sea serpent. Following this, believing that Laocoön was assaulted because he offended the gods, the rest of the Trojans began to accept Sinon's fictional story. Feeling bad for Sinon, and fearing the wrath of the gods, the Trojans brought Sinon and the Trojan Horse into Troy. We all know what happened next.

In keeping with another account by Virgil (Aeneid 2: 57- 198), Sinon wandered until he met with three shepherds and surrendered to them. They, in turn, escorted him to Priam, the king of Troy.

According to Virgil (Aen. 2.79) Sinon (Σίνων) was the son of Sisyphus and a grandson of Autolycus, and because of it, he was a relative of Odysseus. He is described in later poems as having accompanied his kinsman to Troy (Tzetz. ad Lycoph. 344; Heyne, Excurs. iv. ad Virg. Aen. ii.).

Alexander the Great – Strategic Intelligence

Alexander the Great put together a coalition of almost all Greek states, except the Laconians who excused themselves as by tradition they had to lead, not follow another force even if it were a Pan-Hellenic expedition against a common enemy. Alexander had inherited a well-trained fierce Army, which combined with the armies of the current powers as Corinth, Athens, Thebes established an unbeatable force. He only needed a carefully crafted strategic plan that exuded the sense of victory suited to a masterful expedition.

Nevertheless, Alexander the Great had already founded the groundwork for a great plan, Strategic Intelligence. Before he moved against the Persians and Medes, Alexander had ample knowledge of what prudent and visionary generals ought to have on their opponents. He possessed the coup d’oeil, the glance that takes in a comprehensive view what one needs to utilize Strategy, Grand Tactics, Logistics, Engineering, and Tactics along with diplomacy in its relation to War (Jomini 2006, 13 & 337). Alexander knew his adversary but most importantly he knew himself.

In the chapter, “Knowledge of the Enemy - Strategic Intelligence” John Keegan explains that,

Sinon (Σίνων), the Double Agent

As an example of a double agent in the ancient world, but also of selfless dedication to the cause, we take the situation in the Trojan War and the Wooden Horse or as I call it the Greek Horse. His name was Sinon (Greek: "Σίνων"), and he was a relative of Ulysses. Although Homer does not mention Sinon’s name, he does mention the incident with the Horse. Sinon’s name comes to us from Virgil’s book of Aeneid II, 77, but also Quintus of Smyrna. The details of the story appear in Aeneid, book 2, 77, but also in chapter 12 of Quintus of Smyrna in his Post-Homerica.

After Ulysses put the plan down, the task building of the horse was given to an excellent carpenter and skilled boxer (Iliad XXIII) from Phocis, Epeius (Ἐπεύς or Ἐπειός) who told the Greek leadership of the design, the quality and quantity of logs needed for the project. The Greeks went to mountain Ida (presently Turkish: Kazdağı = goose mountain) just southeast of Troy (Turkish Truva) for the timber. Epeius built the horse with a hollow belly so that several warriors could fit in it. We know of the names of 30 warriors who entered the belly of the horse. Epeius was the last one to enter the horse through one of the doors.

After the horse was finished and the warriors entered the hollow horse, the Greek fleet sailed and hid behind the island of Tenedos, but not before they left a wandering warrior at the hills of near Troy. His name was Sinon. Sinon had volunteered for the mission knowing full well that he would be tortured and even killed by the Trojans.

Quintus of Smyrna states that the Trojans woke up in the morning getting ready to attack, but they could not see anyone there except for one man, Sinon, next to the wooden horse. The camp was deserted, and one could see only smoke coming from the Greek campsite. Apollodorus (5.14–5.18) states that Sinon was the one who started the fire only to attract the attention of the Trojans to him.

In the beginning, the Trojans encircled him and gently asked him questions, which he refused to answer. Then the Trojans grew angry and began to threaten him with stabbing. Sinon remained defiant to their threats, not answering their questions. As a means of unfriendly persuasion, the Trojans cut off his ears and then his nose. Finally, under pressure, he told them the pre-rehearsed story, i.e., the Greeks had fled, and they built the Trojan Horse to honor Athena.

According to Quintus of Smyrna (chapter 12), Sinon claimed that Ulysses (Odysseus) wanted to sacrifice him, but he managed to escape and hid in a swamp. When the Greeks gave up looking for him and left, he returned to the Trojan Horse adjacent to the camp. Sinon claimed that out of respect for Zeus, the Greeks stopped looking for him. All the Trojans believe this story, except Laocoön, who, along with his two sons, who were attacked by a giant sea serpent. Following this, believing that Laocoön was assaulted because he offended the gods, the rest of the Trojans began to accept Sinon's fictional story. Feeling bad for Sinon, and fearing the wrath of the gods, the Trojans brought Sinon and the Trojan Horse into Troy. We all know what happened next.

In keeping with another account by Virgil (Aeneid 2: 57- 198), Sinon wandered until he met with three shepherds and surrendered to them. They, in turn, escorted him to Priam, the king of Troy.

According to Virgil (Aen. 2.79) Sinon (Σίνων) was the son of Sisyphus and a grandson of Autolycus, and because of it, he was a relative of Odysseus. He is described in later poems as having accompanied his kinsman to Troy (Tzetz. ad Lycoph. 344; Heyne, Excurs. iv. ad Virg. Aen. ii.).

Alexander the Great – Strategic Intelligence

Alexander the Great put together a coalition of almost all Greek states, except the Laconians who excused themselves as by tradition they had to lead, not follow another force even if it were a Pan-Hellenic expedition against a common enemy. Alexander had inherited a well-trained fierce Army, which combined with the armies of the current powers as Corinth, Athens, Thebes established an unbeatable force. He only needed a carefully crafted strategic plan that exuded the sense of victory suited to a masterful expedition.

Nevertheless, Alexander the Great had already founded the groundwork for a great plan, Strategic Intelligence. Before he moved against the Persians and Medes, Alexander had ample knowledge of what prudent and visionary generals ought to have on their opponents. He possessed the coup d’oeil, the glance that takes in a comprehensive view what one needs to utilize Strategy, Grand Tactics, Logistics, Engineering, and Tactics along with diplomacy in its relation to War (Jomini 2006, 13 & 337). Alexander knew his adversary but most importantly he knew himself.

In the chapter, “Knowledge of the Enemy - Strategic Intelligence” John Keegan explains that,

Alexander the Great, presiding at the Macedonian court as a boy while his father, Philip, was absent on campaign, was remembered by visitors from the lands he would later conquer for his persistence in questioning them about the size of the population of their territory, the productiveness of the soil, the course of the routes and rivers that crossed it, the location of its towns, harbours and strong places, the identity of the important men. The young Alexander was assembling what today would be called economic, regional or strategic intelligence, and the knowledge he accumulated served him well when he began his invasion of the Persian Empire, enormous in extent and widely diverse in composition. Alexander triumphed because he brought to his battlefields a ferocious fighting force of tribal warriors personally devoted to the Macedonian monarchy; but he also picked the Persian Empire to pieces, attacking at its weak points and exploiting its internal divisions (Keenan 2002 – Emphasis added)

Besides his elite cavalry units known as Companions, his Army (infantry, cavalry, peltasts, which is the modern artillery), and his Navy (sea and riverboat fleets), Alexander the Great brought his staff, court officials and their staff, intellectuals, diplomats/envoys, rhapsodes (ῥαψωδοὶ), harpists; jugglers, flutists, guitar players, tragic and comic actors, physicians, seers, engineers, experts on harbors and water/irrigation, suppliers of food, arms, and equipment, architects, surveyors, mining experts, finance officials, recruiters (troop suppliers), military advisers on elephants.

The artists mentioned above provided the necessary entertainment to the troops and their families, something like the modern “rest and recuperation” (R & R), part of the Morale, Welfare and Recreation activities which is significant for the morale and self-esteem of those involved in the expedition.

Over and above those teams, he had enforced his Army’s top cadre with well-known generals and admirals, and their staff not only to ascertain that the campaign worked unhindered by incidental mishaps but also to establish the basis for possible opportunities transferring his own culture to places that Greeks did not know about or they had heard in countless myths. Nevertheless, most importantly, Alexander expecting a long campaign suggested to the above individuals to bring their families with them. And so, they did. It is no wonder that he demolished the Persian Empire only after five battles, the Battle of Granicus (334 BC), the Battle of Issus (333 BC), the Siege of Tyre (332 BC), the Battle of Gaugamela (331 BC), and the Battle of Hydaspes (326 BC).

From the preparation of his operation, the outcome of his undertaking and written material of Greek and non-Greek authors, we conclude that Alexander did not only pursue the destruction of the beast, i.e., the Persian Empire but besides, he engaged in the expansion of the Greek culture over the Persian Empire and beyond. It is why Alexander had gathered all and any information he could that he needed to start his military expedition. Not only he collected information, which he analyzed it, but also, he exploited the information to his advantage. But that was not all. As he advanced, he kept collecting, analyzed, and exploited new information as was subjected to many social, cultural, but also political challenges while he was prosecuting the war against Persians and Medes. He intended to transform all captured regions from the local culture to Greek.

Unfortunately, Alexander passed away before he fulfilled his plan. Jealousy, greed, ambition, fear, corruption, and malfeasance made Alexander’s heirs of his empire aka Diadochi to undermine each other’s legitimacy to the point that vastly contributed to their demise, their kingdom’s downfall, and consequently the decline of the Greek culture in favor of the Romans.

One must never undermine someone else without thinking about the unintended consequences that could follow because one might ruin oneself, and simultaneously the principle one is prepared to defend or advocate. Political upheavals and machinations as a result of selfish intentions, personal ambitions prove fatal for the country, culture, and, of course, the expected cause, regardless of the projected excuse malefactors offer to cover their innermost objectives.

Levels of Intelligence

Collected Information is divided into three different levels of intelligence value, and it is crucial for intelligence analysts involved in the security of the country to recognize them. Generally, there are three ‘levels’ of intelligence value: tactical, operational, and strategic.

Tactical intelligence primarily deals with the current situation and gives customers the information they need to carry out existing policy initiatives, but for a narrow area. This level of intelligence is intended primarily to respond to the needs of military field commanders of company or battalion strength so they can plan for and, if necessary, conduct combat operations. The area of engagement would equate to a town or even township.

That brings us to the next level up, the Operational Intelligence. Operational Intelligence is where the combined actions or even decisions of larger military units like a Brigade or a Division are affected. Operational Intelligence embraces and coordinates several tactical intelligence areas. Information about a military campaign is of operational intelligence significance. The maneuvering of battalions and brigades is of functional intelligence value. It is like such an operational level would equate to a state or a region. Operational Intelligence is actionable information about specific incoming attacks.

Law enforcement agencies rely on tactical intelligence as they obtain important information through individuals or even networks of informants. It is not unusual that the same agencies involved in a broader range of issues continuously without affecting the national or international stage pass the threshold of operational intelligence.

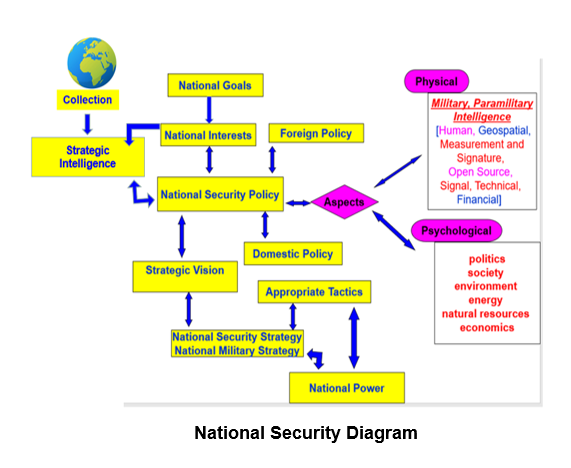

If the issue at hand reaches the national or international arena, then the matter falls under Strategic Intelligence. Strategic Intelligence is the cornerstone of our country’s national security. It involves an array of already analyzed information, i.e., intelligence, coming from all disciplines of intelligence bracing: Foresight, Visioning, System thinking, Motivating, Partnering.

Strategic Intelligence helps the decision-makers of our country to look ahead. Analysis of collected information at that level stimulates dialogue, not only exchanging arguments and counterarguments but also articulating various propositional approaches, such as claiming, inspiring, admitting or retracting a plan among the policymakers. The outcome of such a communication establishes a future policy that could affect either the national interests or the national security of our country or stability of a region or even the world. Regional and global stability is a fundamental prerequisite for peace between peoples and cultures.

Strategic Intelligence expresses the highest-level planning of political and military objectives dealing with national interests and national security because it has national security and foreign policy implications. It provides the policymakers with the information needed to create a new initiative that carries the country forward. One needs to realize that the products of national security of a foreign country come in direct agreement with our national interests since it contributes to regional and perhaps global stability.

The definition of what Strategic Intelligence is was given by Sherman Kent put in his book titled, “Strategic Intelligence for American World Policy.” He wrote,

“Strategic Intelligence is the kind of knowledge a State must possess regarding other states in order to assure itself that its cause will not suffer nor its undertakings fail because its statesmen and soldiers plan and act in ignorance.” (Kent 1966, 3. - Emphasis added)

Early American Spy-Masters

Intelligence played a significant role in the birth and survival of the United States, especially during its infancy. For instance, George Washington, the first President of the United States, was a skillful spymaster. As a military officer, he directed numerous spy networks, “provided comprehensive guidance in intelligence tradecraft to his agents, and used their intelligence effectively when planning and conducting military operations.”

John Jay, one of the three authors of the Articles of Confederation who later became Chief Justice of the United States, is considered the first national-level American counterintelligence chief.

Benjamin Franklin was dexterous in covert operations, and during the Revolutionary War, he engaged in propaganda operations while directing paramilitary operations against the British.

Starting the Country

When a people of a region develop confidence in themselves and feel the ability to govern themselves decide to create a country of their own, they usually write the reasons for their decision. Whether they call the document declarations of independence, reports, acts and manifestos is immaterial since all of such statements rise from the same foundation.

In the U.S. Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson stated that people have certain inalienable rights, including Life, Liberty, and Pursuit of Happiness. All Men are created equal. Individuals have a civic duty to defend these rights for themselves and their posterity.

These were the reasons behind the revolution for independence in 1776. They were the values they cherished. Such values gave rise to the goals that the new country ought to have in order to prosper. It took a few years to establish the final set of government starting with the first Constitution, the Articles of Confederation under which John Hanson, a Finn was the first President of the United States with a term lasting only one year. Following the same articles, seven more presidents followed in subsequent years. In 1789, the founding fathers, replaced the Articles of Confederation with the current U.S. Constitution, which was ratified on June 21, 1788, and went into effect on March 4, 1789.

Therefore, the next step for them was how to achieve the goals through sound policies. Here comes the information needed in order to determine the country’s national interests and secure these interests with appropriate institutions that inaugurate the nation’s national security through sound National Security Strategy and National Military Strategy.

The preamble of the U.S. Constitution sets as goals of the American people "to form a perfect Union" aiming at establishing “Justice, ensure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.”

National Interests in the Ancient World

The Story of Jason

The fight for safeguard a state’s goals based of the prevalent values goes back to antiquity and even to pre-historic times. We see that in the old times, Greeks fully understood the meaning of national interests, although they did not have a collective conscience as one ethnos yet to speak about national security.

The story of Jason, the argonaut expedition, and the golden fleece indicates the resources Greeks were extracting from Georgia. In the case of the golden fleece, it was similar to present-day panning; instead a man the Greeks placed in the water the fleece of the ship. The momentum of the creek or river flowing water created electricity on the wool, which attracted the golden nuggets as they were trapped in the moving sand.

Trojan War

The 10-year long war of Greek city-states against the city of Ilion, aka Troy as Homer narrates in his Iliad, was only a segment of a more significant campaign of interests or as we would describe it “national Interests” of Greek city-states at the time. Although the excuse for the expedition was the abduction of Helen, the reality is that Troy dominated and controlled the straits of Dardanelles as well as the proximal interior of the western part of Asia Minor. It is a fact that Greek city-states had expanded their interests by colonizing coastal areas in the Mediterranean Sea, but also most coastal regions of the Euxine (Black) Sea. The whole issue was a matter of trade between the colonies and their home city. It was a fundamental economic concept involving the procurement and trade of goods and services. Evidently, the Trojans hindered such trade and had possibly imposed some toll or even hindered all navigation forcing the Greeks to retaliate.

Nevertheless, the fact is that not all Greeks were affected in the same way. Some were affected by the hindrance of a trade by the Trojans more than others or not at all due to either alliances or diversion of resources. Those who were affected much more than others had figure out was how to unite all Greeks under a common cause creating a formidable alliance.

As a result, the Greeks who were affected sought an excuse that would unite them against the violator of their trading interests, i.e., Troy. Furthermore, the excuse was the abduction of Helen, which bruised the honor of the King of Sparta Menelaos. It was insulting that a Trojan pirate went into the Palace of a Greek king and stole under the king’s eyes his wife, who happened to be a very beautiful woman. Perhaps Menelaos was not as a famous or powerful king, but his brother Agamemnon was.

The matter was of utmost importance for the Greeks considering that the force and determination of the expedition of a united Greek fleet were 29 contingents under 46 leaders accounting for a total of 1,186 ships (Iliad book 2). If we use the Boeotian figure of 120 men per ship, then the count results in a total of 142,320 men transported to Troy. According to Apollodorus, there were 30 contingents under 43 leaders for a total of 1013 ships of several regions of Greece participated. He lists the participating city-states and their demonyms. Somehow, I doubt that Greek states would mobilize such strength against Troy just for the beauty of Helen and the honor of Menelaos.

The Peloponnesian War

The study of the eight books of Thucydides, summarized under the title “History of the Peloponnesian War,” is imperative for those dealing with strategic concepts as is strategic intelligence. He has recorded political and moral analysis of what today we consider the nation’s policies and the intended or unintended consequences of their outcome. The books include 104 passages that refer to 47 elements of Strategy and Public Policy, among them issues of national interest, strategic culture, and national security.

“The Peloponnesian War” offers passages about alliances, appeasement, arms control, balance of power, balance (external), balance (internal), bipolar international system, border disputes, coercive diplomacy, defense planning, deterrence, domino effect analysis, correlation of economics and strategy, expected utility as an incentive for war, fear, and national security policy, force-to-space ratio, geography, horizontal escalation, hostile feelings-hostile intentions, imperialism, domestic and international legitimacy, logistics, loss-of-strength gradient, military discipline, military initiative, military necessity, military tactics, military training, naval power, morale, strategic culture, national interests, misperceptions, neutrality, numerical superiority, overextension, power, prestige, preventive war, principle of concentration of force, principle of unity of command, reputation as a strategic asset, security dilemma, surprise, terrain, unequal growth. It is why Thucydides is one of the most researched and read author of the ancient world (Koliopoulos 2010, passim).

Such passages establish strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of adversaries. This kind of information helps one to devise methods for identifying data patterns and trends in available information sources. Furthermore, the analyst seeks details to determine changes in adversaries’ capabilities, vulnerabilities, and any probable courses of action.

National Interests in the Modern World

Policymakers aim at defining the national interests of the country by answering several questions and answering them in earnest. Some of the fundamental questions are:

- What are our national goals?

- What must we prevent from happening?

- What should we pursue?

By far, most national interests include, starting with self-preservation through political independence, not in terms of boundaries, but in terms of policies, flourished economy, and military security. Nevertheless, it requires domestic and regional political stability supported by economic constancy and growth while it is safeguarded by the country’s strategic intelligence that supports its national security.

Stability in a democratic state with fully functioning democratic institutions means a predictable political environment, which in turn attracts investment, both internally and from outside. The resulting virtuous circle of poverty reduction, job creation, increased state revenues, and investment in welfare and education bring benefits to all in society such that a return to violence or chaos is in no-one’s interests.

When a country is already in fiscal troubles due to a series of governmental improprieties, e.g., irrational taxation and unreasonable partisan spending aiming at political causes that regress at least 30 years the last thing the country needs is political instability regardless of how good the reason for instability is, as some people might feel. "These people cannot see the forest for the tree.

Obedience to the Law constitutes political behavior just as much as contesting elections does. For whether intended or not, the effect of obedience to the Law is to uphold this authority of those who make decisions about what the Law should be, and how it is to be enforced. To uphold this authority is to aid in maintaining aspects of the distribution of power to make decisions for society. Similarly, all violations of the law constitute political behavior; every violation of law is ipso facto a defiance of constituted authority. It threatens the maintenance of the existing pattern of distribution of the power to make decisions for society. If the incidence of violations of law continue to increase, political authority eventually atrophies; that is axiomatic (Ake 1975 – Emphasis added)

I must explain that the argument for stability applies solely to countries with functioning democratic institutions. It does not apply to autocratic and repressive regimes. Regimes that are led by a dictator or one who believes that laws do not apply to him, domestic stability could lead the country to an oblivion more than one way. For instance, Mobutu Sese Seko, an excellent example of a tyrant, political stability, made him filthy rich. He became notorious for corruption, nepotism, and the embezzlement of between US$ 4 billion and $15 billion during his “reign.”

The Kim family in North Korea, a hard-core communist country in which all peoples are only in theory equal, is another of a hereditary line of governing tin-pot-dictators with delusions of grandeur. Any attempt by the administration of the President of South Korea, Kim Dae-jung, to soften the ruler of North Korea, Kim Jong-Il, by proposing the so-called “Sunshine Policy,” had failed. The obstinacy of the North Korean “Great Leader” and the unification the latter had in mind was a politically stable under his terms and rule. In such cases, political stability is a significant liability to human decency, to say that least.

National interests can be based on the following criteria and more: Ideological, moral, legal, religious, pragmatic, bureaucratic, partisan, racial, class-status, foreign-dependency, and others. In some cases, due to populism, politicians apply the country’s national interests based on sentimentality, often unreasonable.

Once the national interests of a country are defined, the government needs to form or/and join alliances with countries that they consider and pursue similar or identical national interests. A good example of countries caring about their own and regional interests in the formation of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). It started as an administrative agency that was established by a treaty in 1952. I was designed to integrate the coal and steel industries in western Europe. The original participating countries were France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. However, taking into consideration political and economic interests, it developed to the European Economic Community (EEC) and later the European Union (EU).

One must bear in mind that the national goals might change for various reasons as domestic and international circumstances warrant, but the values that founded the country do not; that means that the goals always reflect the values that urged the people to fight for their independence.

Scholars such as Charles Lerche, Abdul A. Said, Vernon Von Dyke, Hans J. Morgenthau, and others have similarly defined national interests. In general, national interests comprise anything a state feels that it is necessary to establish the physical and psychological perimeters of its national security and enhance the welfare of its people. It is a vague definition that requires a lengthy list of needs and wants of the state, which must revisit regularly.

One of the modern devotees of the realist school, Hans J. Morgenthau, wrote “The survival of a political unit, such as a nation, in its identity is the minimum, the necessary element of its interests vis-à-vis other units” (Morgenthau, 1952a, 973).

The Intelligence Process

Individuals

The intelligence analyst gathers information on a specific issue, makes an assessment using an exact intellectual process that transforms a plethora of information into judgments relevant to the formulation of national policies on some issues or topics.

At first, the analyst carefully considers the objective and scope of the assessment. The analyst decides about them on the basis of his background, education, understanding, and any other close association that he might have with the subject matter. If a government official has requested guidance or advice, the analyst concentrates on the issue and articulates his conclusion in a manner that a generalist or an irrelevant person understands it. What is important here is that the analysis as a whole must be free and independent of political considerations.

The analyst must explain the validity of the information and the reliability of his sources. If necessary, he must caveat and express all relevant uncertainties and distinguish between information, assumptions, and judgments. When and where achievable, the analyst incorporates alternative analysis while he establishes relevance to U.S. national security or U.S. allies. In more specific to military cases, he assesses U.S. military operations and capabilities as he assesses the strength and capabilities of adversaries.

Often, the analyst must explain logic and reasoning that led him to crucial judgments, while he must establish “consistency with previous judgments or highlight deviations and justification to protect against factual creep.” Along these lines, he makes accurate judgments and assessments. The analyst never works alone as he seeks and receives advice from his team and joins forces during research and analysis according to time and topic.

On the intellectual side, the standards of an analyst are clarity, relevance, depth, breadth, precision.

It is not unusual that stale, fragmentary, and speculative, and even nefarious and unreliable information is pushed in by politically motivated personnel, most of whom are political appointees to please the boss. Such was the case that led to the invasion of Iraq and a few other adventures (Clarke 2008, passim).

Intelligence Teams

In general, intelligence teams collect information and appropriately interpret it, aiming at concluding the kind of specific information and disseminate it to personnel with expertise in specific disciplines. One-fits-all does not exist in intelligence. It is one of the reasons our intelligence community is compartmented.

Specialized personnel is divided into more specialized management and treatment departments depending on the specialty and geographical area of military interest. Staff is asymmetrically divided into academic disciplines, current needs, experience, and experience in research, analysis, capability, a process utilizing various forms of engagement (productive, inductive, deductive).

To accomplish these tasks, the teams make use of the requisite concentrated information related to research, existing military doctrines, combat, and equipment development and improvements through translations and analyzes that satisfy the potential of multimedia information. Information is collected through geospatial media (satellite and aerial photography), health sources, information collected through interpersonal communication, open sources, signals, scholarly sources, digital networks, financial, cryptanalytical, meteorological, security, and information. Besides, NATO has the "Storm," but also the “Battlefield Information Collection and Exploitation Systems” (BICES) systems.

The analysis of primary data concerns the processing of aggregated information interpreted through a rapid and transparent organization, management, and processing, in order to avoid the accumulation of inaccurate, false, and useless information.

Sources, flow, frequency, quantity, arrangement, and especially the quality of information are taken into account to avoid misleading and misinformation due to emotional and political manipulation.

The credibility of the sources is significant. Rumors, occasions, and conspiracies are always contested. That is why unreliable or questionable sources are not sufficient to establish an event and are treated with great caution when the histories reported are based on entirely hypothetical scenarios.

Finally, team leaders, regardless of grade and grade, meet and put forward partial merging of the conclusions into a general statement. Their focus is on protecting the country's national interests and national security, not protecting the President's political goals. Their oath is to the Constitution and the country against foreign and domestic enemies.

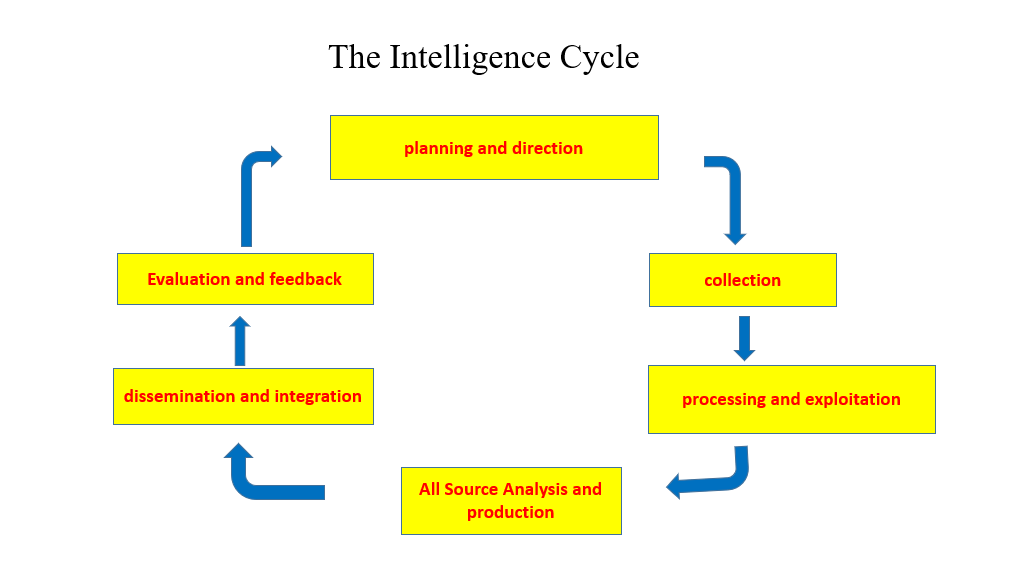

The Intelligence Cycle

I must explain that the process of intelligence never stops. Intelligence professionals call it “the Intelligence cycle.”

The Intelligence Cycle is a concept that describes the general intelligence process in both civilian or military intelligence agencies or law enforcement. The cycle is typically represented as a closed path of activities.

The Intelligence Cycle includes 1. Planning and Direction; 2. Collection; 3. Processing / Exploitation; 4. All Source Analysis and Production; 5. Dissemination/Integration; 6. Evaluation /Feedback.

This cycle never stops, because one must correct any point that did not work for whatever reason simultaneously considering what domestic or international situations influence activities.

Intelligence and National Security

National Security is anything that directly or indirectly affects or violates vital sovereign rights of a country against, and in such a case, the country must react to defend itself. Since it is psychologically connected to the people of the country, it is irrelevant whether other countries agree or disagree with what the country considers issues of national security.

Although countries still use the old and traditional profession of human intelligence to spy on others and deflect their adversary’s espionage, today they rely heavily on technology, which makes it easy for governmental agencies to predict, detect or deflect. Since the establishment of the National Security Act of 1947 that created the (NSC), the intelligence apparatus of the United States has expanded vertically and horizontally. The NSC is the coordinator of the policies and functions of governmental departments and their agencies that relate to all aspects of national security, one of which is the U.S. Intelligence Community. This expansion includes agencies directly under civilian direction and others under military leadership, although under the control of civilian authorities.

The U.S. Constitution does not explicitly concede a formal responsibility regarding the authority of the U.S. Congress to oversee or investigate the executive branch; it implies a responsibility of the U.S. Congress to oversee an array of enumerated powers (Article I, Sec. 8 and Article II, Secs. 2 and 4). Thus, one of them is the Congressional Oversight of national intelligence. It exists to protect the Constitutional rights of our citizens. We, the people, cannot allow the Executive Branch to manipulate received intelligence for political or selfish reasons. In brief, we cannot allow our country to end up in the same situation it existed before 1776 from which the people of the United States decided to be free. We have elected officials, not hereditary potentates, nor we have autocrats.

Some information may also be based on dubious informers with sketchy motives or leaked or stolen documents of unknown origin because they match some person’s beliefs, or even the potentially flawed perceptions of intelligence agents and analysts. It is precisely the reason why a departmental fusion process exists, and agencies propel the information to the Office of National Intelligence, where specific information gets an examination after it undergoes a thorough cleansing.

Assessments on the future of a country regarding its national security come from unexpected, but very unexpected, but relevant sources. A major determining factor of both the structure and operation of institutions of states is the Infant mortality rate. This is a fact. The United Nations keeps track of the Infant Mortality of the world, and intelligence agencies use the infant mortality rate to ascertain the direction of a country’s future. The higher the infant mortality of a country, the gloomier is its future. Primary medical care, a highly nutritional diet, suitable education and a few other essential services that promote the health and welfare of the mothers are vital for the country’s existence. The logic behind it is simple. If a country cannot or will not provide all necessary attention through its institutions to its children, which are the future, the country’s future is questionable.

From the statistical point of view, starting from 1 for the worst and out of 225 countries, the United States ranks approximately 170th depending on the year. Afghanistan holds the 1st position almost invariably while at the end, Iceland competes with Monaco for the best country with the lowest infant mortality.

Intelligence and National Security

National Security is anything that directly or indirectly affects or violates vital sovereign rights of a country against, and in such a case, the country must react to defend itself. Since it is psychologically connected to the people of the country, it is irrelevant whether other countries agree or disagree with what the country considers issues of national security.

Although countries still use the old and traditional profession of human intelligence to spy on others and deflect their adversary’s espionage, today they rely heavily on technology, which makes it easy for governmental agencies to predict, detect or deflect. Since the establishment of the National Security Act of 1947 that created the (NSC), the intelligence apparatus of the United States has expanded vertically and horizontally. The NSC is the coordinator of the policies and functions of governmental departments and their agencies that relate to all aspects of national security, one of which is the U.S. Intelligence Community. This expansion includes agencies directly under civilian direction and others under military leadership, although under the control of civilian authorities.

The U.S. Constitution does not explicitly concede a formal responsibility regarding the authority of the U.S. Congress to oversee or investigate the executive branch; it implies a responsibility of the U.S. Congress to oversee an array of enumerated powers (Article I, Sec. 8 and Article II, Secs. 2 and 4). Thus, one of them is the Congressional Oversight of national intelligence. It exists to protect the Constitutional rights of our citizens. We, the people, cannot allow the Executive Branch to manipulate received intelligence for political or selfish reasons. In brief, we cannot allow our country to end up in the same situation it existed before 1776 from which the people of the United States decided to be free. We have elected officials, not hereditary potentates, nor we have autocrats.

Some information may also be based on dubious informers with sketchy motives or leaked or stolen documents of unknown origin because they match some person’s beliefs, or even the potentially flawed perceptions of intelligence agents and analysts. It is precisely the reason why a departmental fusion process exists, and agencies propel the information to the Office of National Intelligence, where specific information gets an examination after it undergoes a thorough cleansing.

Assessments on the future of a country regarding its national security come from unexpected, but very unexpected, but relevant sources. A major determining factor of both the structure and operation of institutions of states is the Infant mortality rate. This is a fact. The United Nations keeps track of the Infant Mortality of the world, and intelligence agencies use the infant mortality rate to ascertain the direction of a country’s future. The higher the infant mortality of a country, the gloomier is its future. Primary medical care, a highly nutritional diet, suitable education and a few other essential services that promote the health and welfare of the mothers are vital for the country’s existence. The logic behind it is simple. If a country cannot or will not provide all necessary attention through its institutions to its children, which are the future, the country’s future is questionable.

From the statistical point of view, starting from 1 for the worst and out of 225 countries, the United States ranks approximately 170th depending on the year. Afghanistan holds the 1st position almost invariably while at the end, Iceland competes with Monaco for the best country with the lowest infant mortality.

- In 2017 Afghanistan 53.386 deaths per thousand, the United States 5.844 and Iceland only 1.318.

- In 2000, Afghanistan 91.56 deaths per thousand, the United States 7.263 and Iceland only 3.24.

- In 1990, Afghanistan 121.584 deaths per thousand, the United States 9.634 and Iceland only 5.293.

- In 1980, Afghanistan 162.926 deaths per thousand, the United States 13.016 and Iceland only 7.826.

- In 1970, Afghanistan 203.3 deaths per thousand, the United States 20.524 and Iceland only 12.625.

- In 1960, Afghanistan 244.266 deaths per thousand, the United States 26.364 and Iceland only 17.305.

- In 1950, Afghanistan 289.197 deaths per thousand, the United States 31.951 and Iceland only 23.983.

So, what is “Intelligence”? To a man like me who has worked 30 years in that specific field of National Security, intelligence is the analysis of carefully collected information free of contaminated and inaccurate material. It includes objectivity, which is independent of political considerations based on all available credible sources and timeliness.

National security

National security includes everything that has the potential to endanger our country’s existence or way of life. Public institutions can prevent adversaries from using various means to harm our country or its National Interests. Also, it is the confidence of the citizens of the country in their government and established social, political, legal, financial, and other institutions. Once these institutions cease to exist, the country is considered failed, collapsed, and it is why national security is physical but also psychological.

The National Security Council of the country must respond, at least, to the following questions:

- How can we secure our National Interests that we have already achieved?

- How good is the security of our National Interests?

- What can we do better?

- What is our National Security Strategy?

- Is the National Security Strategy efficient for our present needs?

- Is the relation of our National Military Strategy in balance with our National Security Strategy?

- What can we do to improve both?

Although countries still use the old and traditional profession of human intelligence to spy on others and deflect their adversary’s espionage, today they rely heavily on technology, which makes it easy for governmental agencies to predict, detect or deflect. Since the establishment of the National Security Act of 1947 that created the National Security Council (NSC), the intelligence apparatus of the United States has expanded vertically and horizontally. The NSC is the coordinator of the policies and functions of governmental departments and their agencies that relate to all aspects of national security, one of which is the U.S. Intelligence Community. The said expansion includes agencies directly under civilian direction and others under military leadership but under Congressional Oversight.

The U.S. Intelligence Community is composed of 17 organizations:

Two independent agencies

- the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) and

- the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA);

Eight Elements of the Department of Defense

- the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA),

- the National Security Agency (NSA),

- the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA),

- the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO),

- Army,

- Navy,

- Marine Corps, and

- Air Force.

Seven elements of other departments and agencies

- The Department of Energy’s Office of Intelligence and Counter-Intelligence;

- the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Intelligence and Analysis;

- U.S. Coast Guard Intelligence;

- the Department of Justice’s Federal Bureau of Investigation;

- the Drug Enforcement Agency’s Office of National Security Intelligence;

- the Department of State’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research;

- the Department of the Treasury’s Office of Intelligence and Analysis.

Each one of the above organizations and this is true especially of agencies under the Department of Defense, have their branches of specialties. For instance, the Signal Intelligence includes Electronic Intelligence and Communication Intelligence, and each one of them breaks down to their specific technological disciplines. A rather complete list of intelligence gathering disciplines are:

Human Intelligence (HUMINT), Geospatial intelligence (GEOINT), Measurement and signature intelligence (MASINT), Open-source intelligence (OSINT), Signals intelligence (SIGINT), Technical intelligence (TECHNINT), Cyber or digital network intelligence (CYBINT or DNINT), Financial intelligence (FININT). If one adds Cryptanalysis, Meteorological intelligence, Operations Security, Spy satellites, Telecommunications Electronics Materials Protected from Emanating Spurious Transmissions (TEMPEST), and Traffic analysis, Strategic Denial and Deception (D&D) one synopsizes the full scope of intelligence collection.

Let me offer MASINT as an example, so that one understands the complexity of some disciplines of Intelligence.

Measurement and Signatures Intelligence

The Measurement and Signatures Intelligence (MASINT) includes organic sensors that may contain those in everyday use by tactical forces (e.g., radar, electro-optic and infrared, Electronic Surveillance, acoustic, and non-acoustic electromagnetic identification, and may be deployed on air, ground, surface, or unattended platforms). It is, so to speak the CSI of the Intelligence Community. Of course, focusing all disciplines of intelligence to a specific target coupled with information obtained through Human Intelligence, excluding micro-politicking and political appointees subservient to their agendas, our intelligence community is unbeatable.

Quoting from the U.S. Army Field Manual 2-0. Chapter 9, the subdisciplines within MASINT include, but are not limited to, the following:

Radar Intelligence (RADINT). The active or passive collection of energy reflected from a target or object by LOS, bistatic, or over-the-horizon radar systems.

Frequency Intelligence. The collection, processing, and exploitation of electromagnetic emissions from a radio frequency weapon (RFW), an RFW precursor, or an RFW simulator; collateral signals from other weapons, weapon precursors, or weapon simulators (for example, electromagnetic pulse signals associated with nuclear bursts); and spurious or unintentional signals.

Electromagnetic Pulses. Measurable bursts of energy that result from a rapid change in material or medium, resulting in an explosive force, produces RF emissions.

Unintentional Radiation Intelligence (RINT). The integration and specialized application of MASINT techniques against unintentional radiation sources that are incidental to the RF propagation and operating characteristics of military and civil engines, power sources, weapons systems, electronic systems, machinery, equipment, or instruments.

Electro-Optical (E-O) Intelligence. The collection, processing, exploitation, and analysis of emitted or reflected energy across the optical portion (ultraviolet, visible, and infrared) of the EMS.

Infrared Intelligence (IRINT). A subcategory of E-O that includes data collection across the infrared portion of the EMS where spectral and thermal properties are measured.

LASER Intelligence (LASINT). Integration and specialized application of MASINT E-O and other collections to gather data on laser systems.

Hyperspectral Imagery (HSI). A subcategory of E-O intelligence produced from reflected or emitted energy in the visible and near-infrared spectrum used to improve target detection, discrimination, and recognition.

Spectroradiometric Products. Include E-O spectral (frequency) and radiometric (energy) measurements. A spectral plot represents radiant intensity versus wavelength at an instant in time.

Geophysical Intelligence. Geophysical MASINT involves phenomena transmitted through the earth (ground, water, atmosphere) and manmade structures including emitted or reflected sounds, pressure waves, vibrations, and magnetic field or ionosphere disturbances.

Seismic Intelligence. The passive collection and measurement of seismic waves or vibrations in the earth's surface.

Acoustic Intelligence. The collection of passive or active emitted or reflected sounds, pressure waves or vibrations in the atmosphere (ACOUSTINT) or in the water (ACINT). ACINT systems detect, identify, and track ships and submarines operating in the ocean.

Magnetic Intelligence. The collection of detectable magnetic field anomalies in the earth's magnetic field (land and sea).

Nuclear Intelligence (NUCINT). The information derived from nuclear radiation and other physical phenomena associated with nuclear weapons, reactors, processes, materials, devices, and facilities.

Materials Intelligence. The collection, processing, and analysis of gas, liquid, or solid samples.

Over and above the previously stated collection disciplines, one must consider the disciplines of all aspects of Counterintelligence as assembled in Field Manual (FM) 34-60.

Accordingly, when the Intelligence Community of the United States, says “the Russians did it,” it means “the Russians did it,” whether one likes it or not.

Presidential Briefings

The daily Presidential Briefing is part of collective intelligence production and dissemination. It is the result of analyzed information that each agency assembles and disseminates to the ODNI. The ODNI determines what the POTUS must know, and after gathering all 16 one-liners, upholds the most vital information to bring to the attention of the President where selected briefers explain to the President the domestic and global issues of the day in the form of visual aids.

The 21st century began for the United States with rather extraordinary events, which, although directed towards our country, these events have affected the world politically and militarily. While the wars in the Balkans were concluding, the 9/11 attack marked the first remarkable assault on the heart of our country. What followed was the war in Afghanistan and then the invasion of Iraq.

In the last 20 years, the United States has encountered several setbacks in intelligence, not as much because of the rank and file, but because of presidential appointees and politicians who either wanted to please the boss or they considered that some action was needed to show that they were doing something. The only truth in politics is perception, which, by the way, could end up being worse or better than reality.

The emerging challenges and threats of the 21st century are complex and contradictory. They are a far cry from the standard threats we were accustomed to in the past. They are the amalgamation of old antagonisms, ambitions, mingled with advanced technologies having countries or hostile organizations on an equal setting. The prototype of the old times, also known as human intelligence is no longer the only method for a country to learn about their adversaries. Even that type of espionage has changed and has become more sophisticated. It takes 10 to 20 years and sometimes even longer to establish a mutually trusting relationship on both sides. Intelligence collection works based on trust. It is like an alliance or even friendship.

It is why the worst blunder that a decision-maker could make is to treat and implement a well-designed strategic policy as if it were tactical. Everything that was planned and worked for years and years could be destroyed in a matter of minutes. Thus, politicians who relish a short-term gain, they deprive the country and the world of long-term goals, stability, or even long-term solution.

One must always bear in mind that the most significant collection of information and the best analysis in the world means NOTHING if the decision-maker in charge is incapable of understanding facts or unwilling to protect the national interests and, consequently, the national security of our country for a personal gain.

Though, as it happens in our social and business life, our behavior matters also in the international arena as a nation. In politics as well as in foreign relations, our conduct as a country is significant since it tarnishes or enhances our name and reduces or increases our credibility. Intelligence is about planning, while one is ready for the unexpected. Nevertheless, collecting information does not always take place through a cloak and dagger situation. Open sources, like mass media, social media, statistical polls, political or diplomatic receptions, diplomatic instruments, also provide information that trained people can legally gather from free public sources about an individual, organization or country.

An array of websites collects public information about books one checks out of a library, articles in a newspaper or statements in a press release, information in images, videos, webinars, public speeches, and conferences. Collection of information is evident when after research on a matter of interest one keeps receiving snippets exactly on products he had researched in the past with the help of the Internet Protocol address or IP address which offers the actual location of a server or any instrument that requires an IP address.

An IP address information opens the door to the attacker who can use the intelligence created to form a threat model that develops a plan of attack. Targeted cyber-attacks begin with reconnaissance as it happened in 2016, thus testing our readiness to deflect and our resolve by allocating resources to protect our country and its institutions. On the military side, it is passively acquiring intelligence without alerting the target.

Anyone involved in cybersecurity understands how to collect open-source intelligence, which is a vital skill. Whether one defends an enterprise network or tests it for weaknesses, one knows about its digital footprint, which enables one to see it from an attacker’s point of view. Armed with that knowledge, one can go on to develop better defensive strategies.

Conclusion

"Serving in Silence"

Hence as one sees, we collect information, and we advance it to the appropriate persons to start the process and the business of protecting the country. Instead of re-inventing the wheel, I have copied the following from the NSA/CSS website,

“In striving to achieve information superiority for the U.S. and its allies, NSA/CSS is committed to providing accurate, useful information and products promptly to all of its customers throughout the government - from the White House to military forces around the globe. To produce signals intelligence, NSA/CSS intercepts and analyzes foreign communications signals, many of which are guarded by codes and other elaborate countermeasures. By providing security solutions for information systems, NSA/CSS protects information infrastructures critical to national security” (Emphasis added)

Those professionals who have spent their lives defending the country must effectively manage stress since besides keeping every secret that they have learned and know, concurrently, they have to live a normal life. They are husbands and wives with families. They cannot talk about their jobs even to their spouses.

They do their duty to the country without ego, devoid of bombast, and with no reward whatsoever. The satisfaction intelligence officers receive keeping their homeland safe is the greatest reward they can ever have.

The Cryptologic Memorial of the Central Security Service (CSS) within the National Security Agency (NSA) pays tribute to those who gave their lives in the line of duty, "serving in silence." It is a reminder of the crucial role that cryptology plays in keeping the United States secure. It also reminds us of the devotion to Duty, Honor, Courage that these individuals exercised to carry out their mission at such a dear price.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ake, Claude. "A Definition of Political Stability." Comparative Politics 7, no. 2 (1975): 271-83.

Chambers, Donald E. Social Policy and Social Programs. A Method for the Practical Public Policy Analyst. New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1986.

Clarke, Richard A. Your Government Failed You. New York: Harper Collins, 2008.

Crankshaw, Edward. Khrushchev's Russia. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1959.

Dearth, Douglas H., and R. Thomas Goodden. Strategic Intelligence. Theory and Application. Second Edition. Carlisle Barracks, PA: U.S. Army War College. Center for Strategic Leadership, 1995.

Djilas, Aleksa. The Contested Country. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

Djilas, Milovan. Conversations with Stalin. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1962.

Djilas, Milovan. "Yugoslavia: The Outworn Structure." New York Times (CIA Directorate of Intelligence), no. XLVII), Reference Title: Esau; 0048/70, RSS N 0.; 1970, 20 November (October 1970).

Dodds, Anneliese. Comparative Public Policy. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013.

Edward R Stettinius, Jr. Roosevelt and the Russians: the Yalta Conference. Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday, 1949.

Edward R. Stettitnius, Jr. Lend-Lease Weapon for Victory. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1944.

Gerolymatos, André. Espionage and Treason: A Study of the Proxenia in Political and Military Intelligence Gathering in Classical Greece. Amsterdam: J.C. Gieben Publishers, 1986.

J.S. Przemieniecki, Eds. Critical Technologies for National Defense. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio: Air Force Institute of Technology, 1991.

Jović, Dejan. Jugoslavija - država koja je odumrla: uspon, kriza i pad Četvrte Jugoslavije (1974-1990). . Zagreb: Prometej, 2003.

Kardelj, Edvard. Borba za priznanje i neovisnost nove Jugoslavije. 1944-1957. Sećanja . Ljubljana: Drzavna Zalozba Slovenije, 1980.

—. Reminiscences. The Struggle for recognition and Independence: The New Yugosavia 1944 -1957. London: Blond & Briggs, 1982.

Keenan, John. Intelligence in War. The value – and limitations – of what the Military can learn about the enemy. (Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2002.

Kent, Sherman. Strategic Intelligence for American World Policy. Princeton University Press, 1966.

Koliopoulos, Athanassios G. Platias. Constantinos. Thucydides on Strategy: Grand Strategies in the Peloponnesian War and Their Relevance Today. New York: Columbia University Press, 2010.

Lemkin, Raphael. Axis rule in occupied Europe: laws of occupation, analysis of government, proposals for redress. Clark, NJ: Lawbook Exchange., 2008.

Maccoby, Michael. The Leaders We Need, And What Makes Us Follow. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2007.

Moore, David T. Critical Thinking and Intelligence Analysis. Washington, DC: Joint Military Intelligence College, 2006.

Morgenthau, Hans J. "What Is the National Interest of the United States?" The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 282 (1952): 1-7.

—. Another "Great Debate: The National Interest of the United States." The American Political Science Review 46 (December 1952 ): 961-88.

—. In Defense of the National Interest: A Critical Examination of American Foreign Policy. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1951.

Ristović, Milan D. Dug povratak kući: deca izbeglice iz Grčke u Jugoslaviji 1948-1960. Beograd: Udruženje za društvenu istoriju: Čigoja Štampa , 1998.

Rogel, Carole. "The Education of a Slovene Marxist: Edvard Kardelj 1924-1934." Slovene Studies II, no. 1-2 (1989): 177-184.

Roy Godson, James J. Wirtz. Strategic Denial and Deception. New Brunswick, NJ, USA: Transaction Publisher, 2007.

Shafritz, Jay M. The Dictionary of Public Policy and Administration. Univ. of Pittsburgh: Westview, 2004.

Snell, John L. Illusion and Necessity, The Diplomacy of Global War 1939 - 1945. Boston: Houston Mifflin, 1963.

Trittle, Lawrence. "Alexander and the Greeks. Artists and Soldiers, Friends and Enemies." In Alexander the Great. A New History, by Lawrence A. Tritle, Eds. Waldemar Heckel, 121 - 140. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

Tzu, Sun. The Art of War. London: Arcturus Publishing, 2008.

Waltz, Edward. Information Warfare. Principles and Operations. Boston: Artech House, 1998.

Ристовић, Милан. Експеримент Буљкес - Грчка утопија у Југославији 1945-1949. Нови Сад: Платонеум, 2007.

-